Learn About The Aquifer

Educational Materials

What is the Aquifer?

Underground areas that hold enough water to provide a usable supply are called aquifers. Some of the largest aquifers in Texas, including the Ogallala and Gulf Coast, are composed of sand and gravel. In south central Texas, the San Antonio Segment of the Balcones Fault Zone Edwards Aquifer — commonly known as the Edwards Aquifer — is a karst aquifer, which means it consists of porous, honeycombed formations of limestone that serve as conduits through which water travels and is stored underground.

History of the Aquifer

To understand the formation of the Edwards Aquifer, we must first go back 105 million years – to the Age of Dinosaurs. At that time, the region was covered by a shallow sea. That sea held a vast collection of life. Coral, forams, gastropods and other creatures composed of carbonate matter. Algae and calcium carbonate also precipitated from the warm ocean waters forming thick carbonate sediments. 65.5 million years ago, a mass extinction event occurred and almost all of the dinosaurs disappeared (with the exception of birds) and made way for the Age of Mammals.

Over millions of years, plate tectonics resulted in southcentral Texas being uplifted and the Gulf of Mexico to subside. The resulting heat and pressure caused the soft carbonate muds to turn into the hard limestone that forms the Edwards Plateau. The hinge line between the uplifted Edwards Plateau and the subsiding Gulf of Mexico caused the rocks to fracture and fault, forming the Balcones Fault Zone and the southern edge of the Texas Hill Country. The Edwards Limestone that forms the Edwards Plateau has been dropped down by the faults and forms the recharge zone of the Edwards aquifer.

Rainfall absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and from decaying organic material in the soil to form carbonic acid – the same gas found in soda drinks. This weak acid, over millions of years, dissolves the limestone. The water flows through the fractures, faults, and pores in the rock, slowly dissolving it to form conduits and caves. A cave is a natural underground space large enough for a person to enter. A conduit is bigger than the diameter of a hose and smaller than a cave. The area where the rock is fully saturated with water, and can yield sufficient useful quantities is called an aquifer.

Water in an aquifer is part of the hydrologic cycle – the continuous flow of water from the atmosphere to the land surface, stream, rivers, and the ocean to evaporate to form rain. Groundwater is also part of the hydrologic cycle but the movement of water may be much slower than surface streams. In limestone terrains, commonly called karst terrains, water may flow beneath the surface in caves to emerge at springs. Groundwater velocities can be much faster in karst terrains than in other aquifer types such as sand and gravel aquifers. Karst aquifers are characterized by the presence of soluble rock, caves, sinkholes, sinking streams, and springs. The Edwards Aquifer is a karst aquifer and is noted for rapid recharge of water and rapid groundwater velocities in the recharge zone. Groundwater velocities have been measured at more than a mile per day in some areas.

Water from the surface sinks into the ground through fractures, sinkholes, and caves in limestone to form the Edwards Aquifer. Water discharges from a series of springs including Comal and San Marcos springs, the two largest springs in the southwest. The flow of water into and through the aquifer creates a positive feedback loop – water containing carbonic acid slowly dissolved the rock which allows more water to enter the aquifer which dissolved more rock – which allows more water to enter the aquifer and so on. To observe the limestone dissolved in water from the Edwards Aquifer, boil a pot of water until the pan is empty and observe the white material left in the pot. This is the dissolved Edwards Limestone.

Where is the Aquifer Located?

The Edwards Aquifer is an artesian aquifer located in Central/South Texas. From the western-most reaches of our region in Uvalde County to points east in Hays County and many places in between, the Edwards Aquifer is the natural water resource that supports approximately 2.5 million people.

The Edwards Aquifer Authority is responsible for a jurisdictional area that covers more than 8,000 square miles across eight counties in south-central Texas, including all of Uvalde, Medina, and Bexar counties, plus portions of Atascosa, Caldwell, Guadalupe, Comal, and Hays counties.

How Does the Aquifer Work?

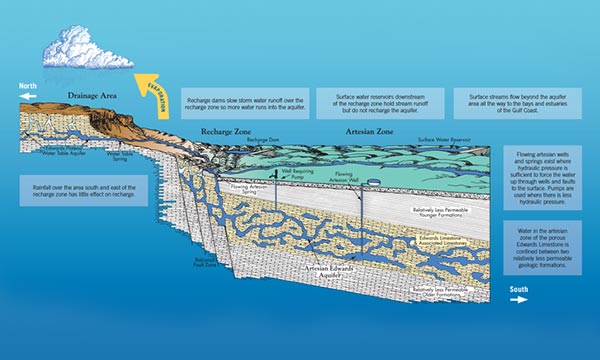

This generalized diagram of a north-south cross section of the Edwards Aquifer region highlights the key components of the aquifer and how they inter-relate and function to form a natural underground system for storing water.

The Edwards Aquifer is a karst aquifer, which means it consists of porous, honeycombed formations of Edwards Limestone and other associated limestones that serve as natural conduits through which water travels and is stored under ground.

Water reaches the aquifer as rain runoff that first collects on the contributing zone (Edwards Plateau), soaks into the water table, and then emerges as spring-fed streams that flow downhill to the recharge zone. In the recharge zone, where the Edwards Limestone is exposed at the land surface, the water actually enters the aquifer through cracks, crevices, caves, and sinkholes, and then percolates further underground into the artesian zone. Here, a complex network of interconnected spaces, varying in size from microscopic pores to open caverns, stores and carries water in a west to east direction. Because water in the artesian zone is under pressure, there are areas where water is forced back to the surface through openings such as springs and free-flowing wells. Where there is not enough artesian pressure to force water to the surface, wells equipped with pumps can extract water from the aquifer for human use.

Conditions

Conditions

CURRENT

CURRENT